AS soon as I stopped in front of a flat in Sen Sok district, I could hear a song playing inside. In the song, a man described his struggle to become a star by leaving his family, relatives and friends in the provinces and coming to the city to pursue his dream.

AS soon as I stopped in front of a flat in Sen Sok district, I could hear a song playing inside. In the song, a man described his struggle to become a star by leaving his family, relatives and friends in the provinces and coming to the city to pursue his dream.

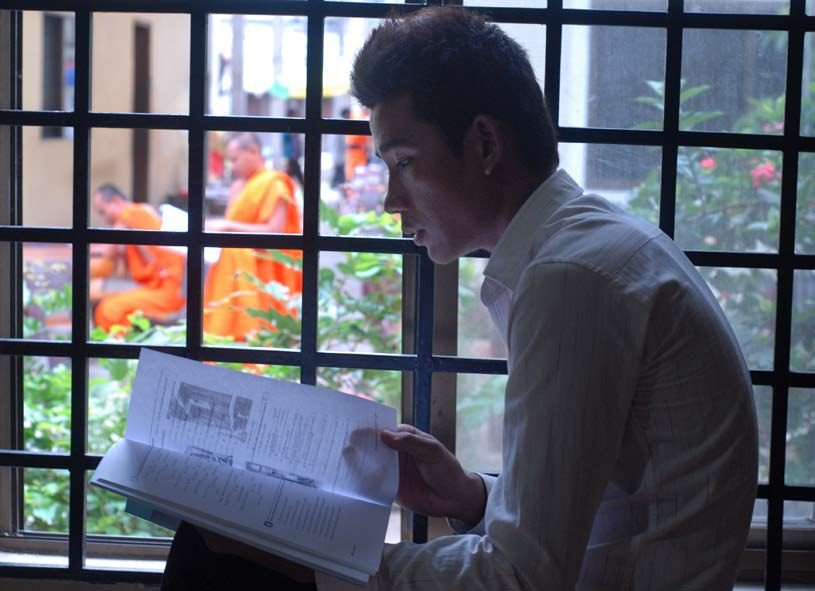

When I opened the door to the flat, there was a young man sitting on a plastic chair playing an electric guitar and singing along to the song playing on a nearby CD player. It was Morm Doungseth, our youth of the week for this issue.

While turning off the CD player and putting his guitar next to a big electric keyboard, Morm Doungseth told me the song I had just heard was one he had written to reflect his life story. He said he had just finished recording the song using his CD player, and with no musical instruments other than his guitar and his voice.

Morm Doungseth, 18, has been working as a singer for Mohahang, a Cambodian music production house, for almost six months. Six songs by him, produced by Mohahang, can be found in markets; others are waiting in the queue to be included on forthcoming albums.

Morm Doungseth left his home town in Kampot province for Phnom Penh in 2008 and got into the music industry a few months later. “I’ve loved music since I was young, and in my free time I listened to all kinds of music and sang along,” he says.

“After my friends and my older brother saw I had talent, they encourage me. Since then, I have focused my efforts on music .”

Since he arrived in Phnom Penh, Morm Doungseth has worked as a DJ and singer in various nightclubs. But he doesn’t want to spend his whole working life doing that, so he’s seeking an opportunity to become a professional singer.

He sent an application to Mohahang, and at the same time joined a singing competition at Bayon TV. He left the competition at Bayon TV after being selected to be a signer at Mohahang, even though he had almost reached the final round of the contest.

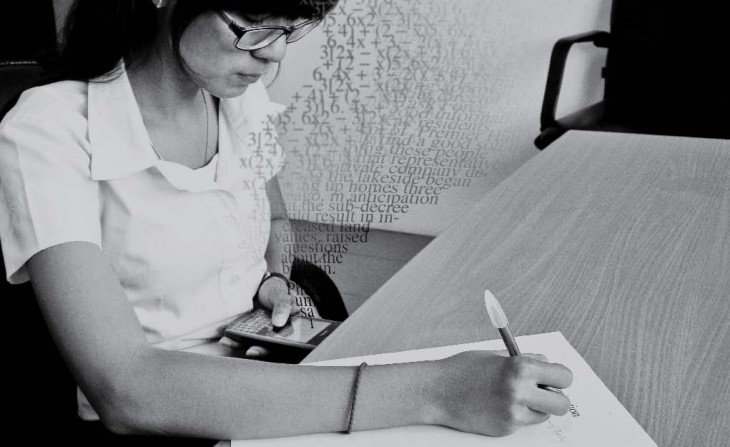

As well as singing, Morm Doungseth can play guitar and keyboards, because he studied at the Royal University of Fine Arts in 2009 and 2010. Working while studying will lead to problems if a student fails to manage his or her time well. As well as being a singer who is gaining more recognition every day, Morm Doungseth will be a grade 12 student in the next year.

“I won’t let my career interfere with my studies,” he says, adding that he always gives priority to study. “I study in the morning, I go to the company in the afternoon, and I review my lessons at night,” he says of his time-management plan.

“I will pursue a bachelor’s degree in English literature, because I love that subject, and in the future I will choose a job based on the subject I have studied, while working part-time or occasionally singing because that’s my favourite thing and my natural talent, so I shouldn’t throw it away.”

01/09/2011 By: Dara Saoyuth This article was published on LIFT, Issue 86 published on August 31, 2011